<oo>→<da>→<le> Digenis Akritis: Lay

of the Emir

About this site

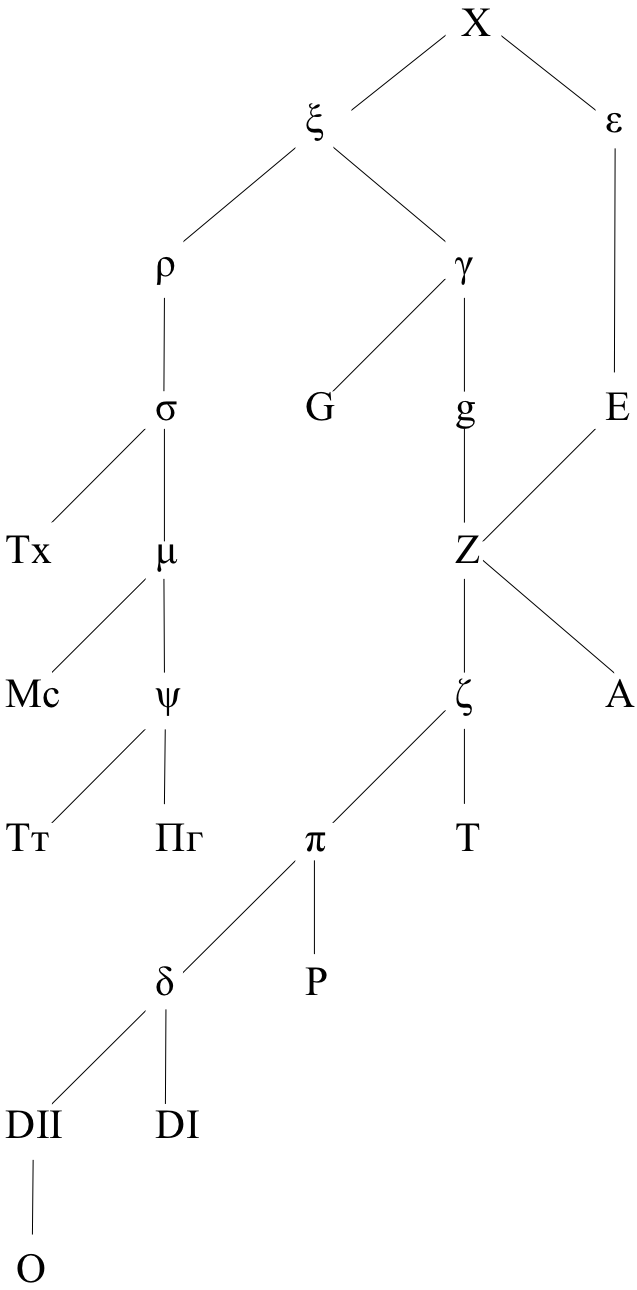

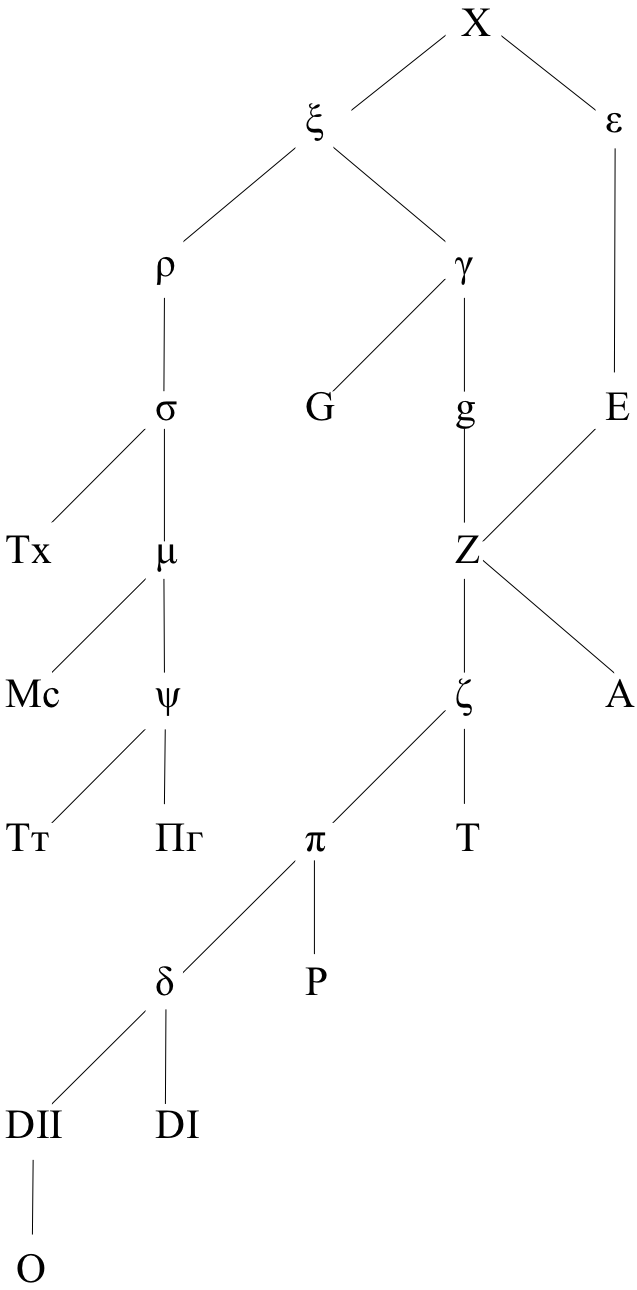

This edition represents a part of the efforts of one of the authors (Robert Romanchuk) to

produce a critical edition of the Slavic version of the 12th-c. Byzantine romantic

epic

Digenis Akritis, reliable enough for Slavists interested in the work’s life

and reception from the 14th c. to the 18th, but also of use to Byzantinists. If in 1978

Michael Jeffreys, in despair about the difficulty of progress

on questions around

the Slavic text, proposed that it be treated with the same caution as Akritic

folksongs collected in the 19th c., and if twenty years later its continued

problematic

status allowed it to be left out of account

in Elizabeth

Jeffreys’s magisterial edition of the two oldest Greek versions—the failed romance in MS

Grottaferrata (or G) and the approximated epic in Escorial (or E)—then

today these questions are well on their way to being resolved.

We have

known for some time that Henri Grégoire was in error by aligning the Slavic

Digenis (in its earliest form, Erich Trapp’s version ρ) with the

prototype of the work. Yet neither is the Slavic version ρ the transcription of

an oral epic, as some Byzantinists still imagine, nor is it a reflex of the 16th-c.

omnibus version Z, as John Mavrogordato supposed. Rather, it is a distant cousin

of G, as Trapp showed in his synoptic edition of the Greek versions. Moreover,

and against the majority opinion in the Slavic field, ρ is almost certainly not

Rusian (East Slavic), but was most probably produced in bilingual and bicultural 14th-c.

Macedonia—as André Vaillant proposed—in the era of Stefan Dušan. In places ρ

shadows G line for line and word for word, reflecting Trapp’s hyparchetype

ξ, shared ancestor of G and ρ, better than does G: e.g.,

ρ lacks the gnomic interpolations of G, as does Z; ρ

also preserves certain oral-traditional formulas of the prototype in their original

form, as Trapp demonstrated. But in many places ρ has been reworked from ξ

in an oral-formulaic mode, far more radically than E has been.

We have

known for some time that Henri Grégoire was in error by aligning the Slavic

Digenis (in its earliest form, Erich Trapp’s version ρ) with the

prototype of the work. Yet neither is the Slavic version ρ the transcription of

an oral epic, as some Byzantinists still imagine, nor is it a reflex of the 16th-c.

omnibus version Z, as John Mavrogordato supposed. Rather, it is a distant cousin

of G, as Trapp showed in his synoptic edition of the Greek versions. Moreover,

and against the majority opinion in the Slavic field, ρ is almost certainly not

Rusian (East Slavic), but was most probably produced in bilingual and bicultural 14th-c.

Macedonia—as André Vaillant proposed—in the era of Stefan Dušan. In places ρ

shadows G line for line and word for word, reflecting Trapp’s hyparchetype

ξ, shared ancestor of G and ρ, better than does G: e.g.,

ρ lacks the gnomic interpolations of G, as does Z; ρ

also preserves certain oral-traditional formulas of the prototype in their original

form, as Trapp demonstrated. But in many places ρ has been reworked from ξ

in an oral-formulaic mode, far more radically than E has been.

What is more, half of ρ—including the opening Lay of the Emir

, the episode

treated by this site—is extant only in the 17th-c. Muscovite (Russian) abridgment

ψ (Kuz′mina’s second redaction

) that reorders entire sections of plot,

deletes descriptive passages, and further folklorizes

the text. The Slavic

Lay

is something of a narrative chaos in the abridgment, at least from the

point of view of the Greek versions that preserve the original ordering. When an episode

is extant in both the 14th-c. ρ (in the form of MS Тх) and the 17th-c.

abridgment ψ, plot material from the former may be freely reordered in the

latter: thus, in the education and hunt scenes that open the Romance of Digenis

episode, the Muscovite editor moves the dove-white horse that the hero gains at the end

of his investiture to the very beginning; inverts the order of killing the bears and the

deer (in Slav, a moose), forgetting about the he-bear in the meantime; and eliminates a

great deal of description and dialogue besides.

In 2015, making use of Roderick Beaton’s 1993 reconstruction of the common core

of

the Lay of the Emir

(which he based on his close comparison of MSS E and

G), Robert Romanchuk and his FSU Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program

assistant Thuy-Linh Pham recovered the probable original (Greek) ordering of the Slavic

material of the Lay

preserved in the abridgment ψ. The present site shows

the ordering of Beaton's core

; Romanchuk and Pham’s reconstructed (hypothesized)

ordering of the Lay

in ρ, which follows the core

; and the Muscovite

editor’s shuffling

of narrative passages in ψ, in a holistic visualization

of their interrelationships known as a plectogram (the invention of Hugh Olmsted).

Large parts of the ρ narrative have been reordered in the Muscovite abridgment

ψ. First, most of passages ibis to 9bis (the youngest brother’s

combat with the Emir, his defeat and his lies to the brothers, which motivate the scenes

that follow) have been swapped with passages 10 to 21 (the brothers’

interrogation of the Saracen at the tents of the Emir’s army, their discovery of the

slaughtered Christian maidens and angry return to the Emir). Thus in the abridgment, the

brothers meet their informant at the tents even before encountering the Emir himself.

Characteristically for Slav, this Saracen is hypertrophied into an army of 3000, quickly

cut down to three, who, in the abridgment, lead them to the Emir instead of the girls.

At passage 8 in ψ, a bout of folkloric boasting (Stith Thompson's motif

W117) is interpolated: Tell us, Emir, have you no guards posted on the way? We

reached the tent without any resistance

(MS Тт, f. 173v). The duplicated

but now tell us

bears witness to the motif papering over the seam.

At a finer level of detail, passages 23 (the brothers’ final threat) and

25–26 (the Emir’s offer to convert and marry the girl) have inexplicably been

inverted from the ordering of the Greek core

. To help the Muscovite reordering

cohere, the motif of association of equals and unequals (J410) enters passage 23:

How can we give our sister to a slave?

(f. 175v). This passage is generally

supposed to belong to the Muscovite editor, as it makes use of the East Slavic

vernacular form kholop.

The second large-scale reordering of the narrative is an exchange of passages 63

to 70, the Emir’s intent to visit Syria (in ρ, his trip to Arabia

),

with most of passages 35 to 52, his mother’s threatening letter, which

motivates the Emir’s journey in the first place! And the birth of Digenis

(33bis–34), which in the original ordering follows the Emir’s conversion and

wedding to the girl, has been postponed to the end of the abridgment’s Lay

. In

these cases too, folkloric material (motifs P678; M301.4, M311[.0.2.1]) are employed to

stitch the narrative back together.

The Muscovite reworking of the plot of the Lay of the Emir

has a marvelous basis.

Its logic appears to be that of Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the folk

wondertale: all tests of the heroes (e.g., finding the dead girls) are now

grouped before the struggle with the villain (single combat with the Emir)—in Propp’s

algebra

, sequences DEF precede sequence HI; while the mother’s

letter, rather than motivating the Emir’s visit, is here treated as a villainous pursuit

of the hero in response to his completing the difficult task of his journey—that is,

Propp’s sequence PrRs follows sequence MN. And the hero’s reward W,

the birth of his son, is at the end of the tale, where the wondertale demands it.

![Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 Unported License [Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 Unported License]](https://obdurodon.org/images/cc/88x31.png) Last modified:

2026-02-07T17:14:04+0000

Last modified:

2026-02-07T17:14:04+0000

We have

known for some time that Henri Grégoire was in error by aligning the Slavic

Digenis (in its earliest form, Erich Trapp’s version ρ) with the

prototype of the work. Yet neither is the Slavic version ρ the transcription of

an oral epic, as some Byzantinists still imagine, nor is it a reflex of the 16th-c.

omnibus version Z, as John Mavrogordato supposed. Rather, it is a distant cousin

of G, as Trapp showed in his synoptic edition of the Greek versions. Moreover,

and against the majority opinion in the Slavic field, ρ is almost certainly not

Rusian (East Slavic), but was most probably produced in bilingual and bicultural 14th-c.

Macedonia—as André Vaillant proposed—in the era of Stefan Dušan. In places ρ

shadows G line for line and word for word, reflecting Trapp’s hyparchetype

ξ, shared ancestor of G and ρ, better than does G: e.g.,

ρ lacks the gnomic interpolations of G, as does Z; ρ

also preserves certain oral-traditional formulas of the prototype in their original

form, as Trapp demonstrated. But in many places ρ has been reworked from ξ

in an oral-formulaic mode, far more radically than E has been.

We have

known for some time that Henri Grégoire was in error by aligning the Slavic

Digenis (in its earliest form, Erich Trapp’s version ρ) with the

prototype of the work. Yet neither is the Slavic version ρ the transcription of

an oral epic, as some Byzantinists still imagine, nor is it a reflex of the 16th-c.

omnibus version Z, as John Mavrogordato supposed. Rather, it is a distant cousin

of G, as Trapp showed in his synoptic edition of the Greek versions. Moreover,

and against the majority opinion in the Slavic field, ρ is almost certainly not

Rusian (East Slavic), but was most probably produced in bilingual and bicultural 14th-c.

Macedonia—as André Vaillant proposed—in the era of Stefan Dušan. In places ρ

shadows G line for line and word for word, reflecting Trapp’s hyparchetype

ξ, shared ancestor of G and ρ, better than does G: e.g.,

ρ lacks the gnomic interpolations of G, as does Z; ρ

also preserves certain oral-traditional formulas of the prototype in their original

form, as Trapp demonstrated. But in many places ρ has been reworked from ξ

in an oral-formulaic mode, far more radically than E has been.